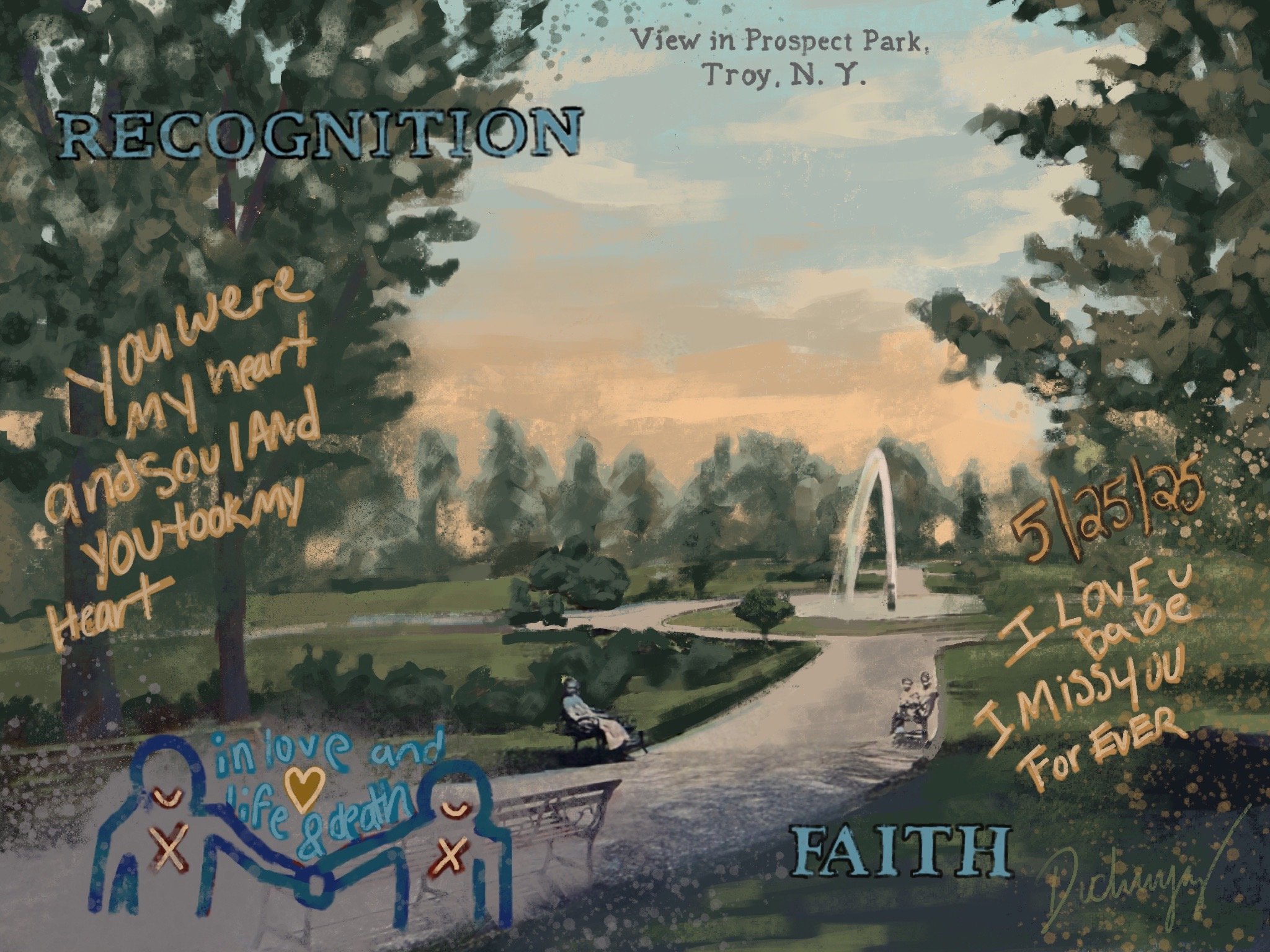

Views of Prospect Park

Prospect Park in Troy, New York was established in 1903 and designed by Garnet Douglass Baltimore, the first African American graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). The land was once known as Mount Ida, where Samuel Wilson and his brother built a farmhouse and ran a meat-packing business. This business supplied meat to American soldiers during the War of 1812, when troops began joking that their food came from “Uncle Sam.”`

Baltimore advocated for the acquisition of the Mount Ida property in the 1890s because of its incredible views of the Catskill Mountains. At the time, city officials were skeptical—one city leader even referred to public parks as “gathering places of vagrants and hoodlums”. Despite this, the city purchased the Warren property atop Mount Ida for $110,000.

The park was constructed with an artificial lake and fountain, winding pathways, flower beds, tennis courts, an overlook tower, and an elaborate bandstand. The Vail House was converted into a casino, and the Warren Mansion became a public museum and community building.

Prospect Park thrived during the early 20th century, as Troy’s industries—like steel and collar production—reached their peak. But by the Great Depression, city resources were strained. The Warren Mansion was demolished, and ten years later, the Vail House (Casino) burned down and was never rebuilt.

Troy’s population declined dramatically due to post-industrial suburbanization. Discriminatory New Deal housing policy segregated access to affordable housing. Known as “white flight,” middle class families left Troy for suburbs like Latham, Colonie, Brunswick, and East Greenbush. The housing crisis in Troy left behind sharp economic and racial divisions which weakened city services. During this period, there were efforts to revive the park—basketball courts were added, along with the above-ground Blintz pool, which has been abandoned since 1992.

These historical echoes shape the way we experience Prospect Park today-layered, weathered, and alive. Visual art allows us to romanticize the everyday, and in this series, I explore the park's evolving landscape through quiet observation and reverence.

Rendered in charcoal, oil paint, digital drawings, gouache, and watercolor, these artworks reflect not only the passage of time but also the quiet persistence of place. These artworks focus on the park as it exists today: layered, imperfect, and alive. Faded signs, cracked pavement, and graffiti mark the space. They aren’t nostalgic renderings of a lost era, but quiet observations of a space that continues to shift and endure.

Suzanne Spellen, “Troy New York History & Architecture: Garnet Baltimore,” Brownstoner, July 2, 2024